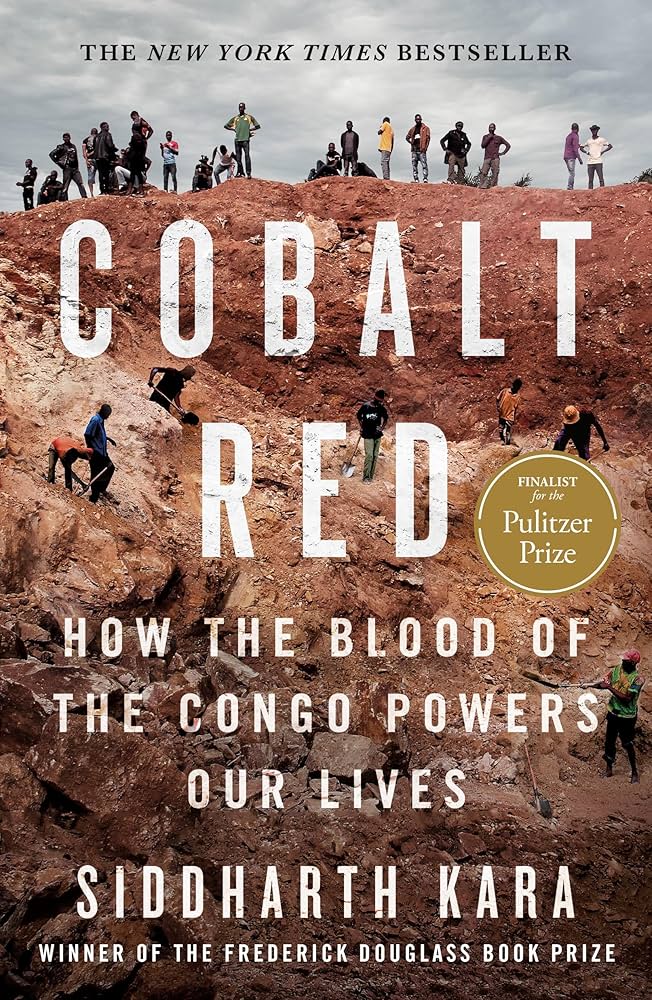

Cobalt Red by Siddharth Kara exposes the hidden human and environmental costs of cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which supplies most of the world's cobalt for smartphones, laptops, and electric cars. Kara traces the story from Congo's brutal colonial past under King Leopold II to today's scramble for cobalt, showing how the system still mirrors slavery: children and adults dig in perilous hand-dug tunnels for a few dollars a day, while corporations reap vast profits. Villages vanish, rivers are poisoned, and lives are lost, despite repeated promises from companies like Apple, Tesla, and Samsung about "responsible sourcing". The book blends history, on-the-ground reporting, and personal testimonies to reveal how the global supply chain hides this violence, much like Europeans once ignored that their sugar came from enslaved Africans. Yet amid the suffering, Kara insists there is hope: if consumers recognize that the child who dies in a Congolese mine is part of the same human family, they may finally demand change.

Unspeakable Richness

Kolwezi, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), sits at the center of the world's cobalt supply, providing the metal that powers smartphones, laptops, and especially electric cars. Without Congolese cobalt, modern technology would grind to a halt. Yet cobalt is mined in some of the harshest conditions on earth: children and adults dig with their bare hands or simple tools in toxic pits and tunnels, earning just a dollar or two a day while facing constant risk of injury or death. The land is devastated, rivers are poisoned, and communities are erased. Despite promises of "responsible sourcing", global giants like Apple, Tesla, Samsung, and BMW rely on a supply chain built on hidden suffering.

This reality is not new. For centuries, Congo's wealth in ivory, rubber, diamonds, uranium, copper, and now cobalt has been stripped away by foreign powers and corrupt leaders, leaving the Congolese people among the poorest in the world. The riches of Katanga, worth trillions, could fund schools, hospitals, and clean water, yet the national budget remains tiny, and life expectancy is low. Families unable to pay school fees send children to the mines, where they earn pennies while fueling billion-dollar industries abroad. In this way, cobalt continues the long-standing colonial pattern: resources are extracted for the world's benefit, while the people who live on the land remain trapped in poverty.

Global demand ensures the cycle deepens. Artisanal miners, known as creuseurs, supply as much as a third of Congo's cobalt, which is mixed with industrial output in depots and shipped mainly to China for refining. From there, cobalt becomes a key component in batteries, fueling the explosive growth of electric vehicles and renewable technologies. Companies are experimenting with reducing cobalt use, but for now, the world remains dependent on Congo's shallow deposits, which are easy to dig by hand. Until demand slows or alternatives emerge, the "clean energy" revolution will carry a dark stain, built on the backs of miners in Kolwezi, whose daily risk and suffering make possible the devices and cars that define modern life.

Here It Is Better Not to Be Born

Lubumbashi, the main city in southeastern Congo, has long been tied to the exploitation of copper and cobalt. From the time Belgium created Union Minière du Haut-Katanga in 1906, the region's minerals fueled foreign wealth while leaving Congolese people in poverty. The legacy of forced labor, violent secession attempts, and colonial control still shapes the city, where today Chinese and other foreign companies dominate mines like Ruashi and Étoile. Villagers living around these sites earn barely a dollar a day, lack schools, electricity, or clean water, and face constant displacement as mines expand. The scars of history remain visible in the land and in the lives of the people who still suffer under the weight of foreign exploitation.

The city itself is vibrant and bustling, filled with markets, churches, and small businesses, but it is also marked by military checkpoints and corruption. Access to mining areas requires navigating layers of suspicion, soldiers, and bureaucracy. With official backing, the author was able to visit mining communities and hear firsthand accounts of their struggles. Students in Lubumbashi spoke of miners treated "like slaves", forests destroyed, and rivers poisoned. They warned that unless resource wealth was invested in people, Congo's future would collapse under poverty and ignorance. While President Tshisekedi has since promised to fight corruption and renegotiate unfair deals, ordinary miners have yet to see improvements.

A detour to Kipushi revealed the stark divide between industrial and artisanal mining. While foreign-run companies use advanced technology, thousands of men, women, and children nearby dig by hand, earning less than a dollar a day while exposed to toxic dust and frequent violence. Families work together out of desperation, selling their ore at a low price to middlemen who profit without risk. Health studies show shocking levels of contamination in miners and even in people who simply live near these sites. Local and international organizations claim to fight child labor and promote clean cobalt, but on the ground, little changes. Poverty drives families into the mines, while global companies benefit from cheap resources. In the end, the people of Congo pay with their health, their land, and often their lives, while the rest of the world enjoys the devices and cars powered by their suffering.

The Hills Have Secrets

After returning from the Congo, the author struggles with the contrast between the daily comforts of the West and the misery that makes them possible. Congo's cobalt mines, like earlier eras of slavery and colonization, continue a long history of Africa's exploitation. At a Chinese club in Lubumbashi, a manager at Congo DongFang Mining mocked Africans as lazy and incapable, reflecting the racist attitudes of those profiting from Congo's wealth. The suffering in the mines is not new; it is simply the latest chapter of a system where Congolese people pay the price so the rest of the world can enjoy modern life.

On the road to Likasi, villages reveal deep poverty despite being situated on the richest deposits of cobalt and copper. Families live without electricity, children haul water, and soldiers harass travelers. In Likasi and the surrounding hills, artisanal mining is the dominant activity. Men, women, and children dig and wash stones in dangerous streams, suffering from rashes, coughs, and exhaustion. Many children, trafficked or pushed out of school by fees, spend their days in the mines. The cobalt they dig ends up in depots and is sold to Chinese companies, feeding global supply chains while the miners themselves remain trapped in hunger and misery.

Further north in Kambove, the cycle of exploitation repeats itself. A century ago, King Leopold's system of forced extraction was exposed to the world, but little has changed. After independence, Congo's state mining company once provided jobs, housing, and schools, but corruption and foreign deals destroyed it. Now, Chinese companies and local elites profit while families work for a dollar or two a day, with no safety, food, or education. In remote hills, children and young mothers dig with babies strapped to their backs, sometimes forced by militias. Soldiers control access, and deaths are hidden in silence. The cobalt from these sites, mined under conditions of poverty and fear, continues to flow into the batteries that power the world's phones and electric cars.

Colony to the World

The author argues that Congo's greatest danger is not only poverty, violence, or mines, but its long history. Since Europeans first arrived at the mouth of the Congo River in 1482, the country has been trapped in cycles of slavery, colonization, and exploitation. Millions were taken as slaves from Loango Bay, and later, King Leopold II of Belgium tricked chiefs into signing away their land, making Congo his personal property in 1885. Under Leopold's rule, villagers were forced into brutal rubber collection, with horrific punishments for failing quotas. Even after Belgium took over in 1908, exploitation continued through mining and forced labor for foreign companies.

When Congo finally gained independence in 1960, hope was short-lived. Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister, denounced Belgium's cruelty, but within months, he was overthrown and killed with the support of Belgium and the US. His death destroyed the country's chance at real freedom. What followed were decades of dictatorship under Mobutu, who stole billions while the US and Europe supported him during the Cold War. After Mobutu's fall, Congo descended into wars involving multiple countries, with millions killed and minerals traded for weapons and power. Leaders from Laurent Kabila to his son, Joseph Kabila, continued the cycle of corruption, selling off mining rights while the people remained poor.

Today, Congo remains at the center of global struggles over cobalt, copper, and other minerals. Chinese companies dominate much of the mining, while Western powers compete for influence. Presidents promise reforms, but corruption and foreign exploitation continue. For ordinary Congolese, little has improved: they still live in poverty while their land produces the minerals that power the world's technology and clean energy revolution. History, like the Congo River, continues to shape the present, making it difficult for the country to break free.

If We Do Not Dig, We Do Not Eat

Traveling west from Likasi toward Kolwezi shows the heavy cost of Congo's cobalt trade. The roads are jammed with trucks carrying minerals, motorbikes stacked with ore, and fuel sellers exploiting shortages. Dust, smoke, and pollution choke villages along the way, leaving children to play in toxic clouds and land stripped of nature. This is Lualaba Province, home to some of the world's biggest cobalt mines. Companies insist that industrial and artisanal mining are separate, but in reality, the two are deeply connected. Industrial sites often rely on artisanal labor, and once cobalt enters the supply chain, it is impossible to trace where it came from.

At Tenke Fungurume, one of the largest mines in the world, villagers were evicted from their land and left with no fair compensation. Now controlled by the Chinese company CMOC, the mine produces vast amounts of cobalt, but locals see little benefit. Many sneak back into the concession to dig by hand, selling ore to depots that quietly feed it into the company's exports. The result is constant conflict, broken promises of jobs and schools, and daily exposure to dust and chemicals. Mutanda, another giant mine run by Glencore, shows the same pattern. Even after the company shut it down, nearby Shabara grew into one of the largest artisanal mines in Congo, with tens of thousands of men and boys digging by hand for a few dollars a day, supplying cobalt that ends up in global markets.

Tilwezembe exposes the darkest side of this system. Though owned by Glencore, it is now almost entirely run by artisanal miners, including thousands of children. Many work in deadly tunnels with no safety gear, trapped in debt to bosses, and constantly threatened by soldiers. Injuries and deaths are common; teenagers are crushed in collapses, boys lose limbs, and families mourn lost children. Despite global promises of "responsible sourcing", cobalt from Tilwezembe and sites like it still flows into the supply chain. For many families, the truth is simple: if we do not dig, we do not eat.

We Work in Our Graves

Kolwezi, in the southeast of Congo, is the center of the world's cobalt rush. A quarter of global reserves lie here. However, the city is scarred: open-pit mines, toxic lakes, and destroyed villages dominate the land, while slums grow around the mines. The population has exploded to over a million, yet most live in poverty, pressed against polluted pits. Soldiers, militias, and corruption shape daily life, and violence often follows protests. Despite promises of jobs and schools, locals are left with dust, hunger, and fear, while companies like Glencore and Chinese firms reap the profits.

Around Kolwezi, different neighborhoods show the harsh realities of mining. In Kapata, families and children dig by hand, often washing ore in poisoned water. At Lake Malo and Mashamba East, women earn barely a dollar a day washing stones, while boys risk falls in tunnels. Soldiers sometimes force children to dig for them, taking the profits. In Kanina and at Lake Golf, women and children wash cobalt for cents, while guards and middlemen profit. Traders, whether Chinese buyers, Lebanese fixers, or soldiers, dominate depots like Musompo, where cobalt from child labor and unsafe pits is mixed into the global supply chain. Even "model mines" like CHEMAF's Mutoshi and CDM's Kasulo, backed by big tech, quietly fail their promises, with children sneaking in, miners trapped in debt, and "clean" cobalt mixed with ore from dangerous sites.

For families, survival depends on digging. Tunnels in Kasulo run under homes, collapsing often and killing miners whose bodies are never recovered. Widows like Jolie mourn husbands and sons buried alive, while survivors like Lucien live crippled with no medical care. Children are forced into mines instead of schools because the fees are too high. Some are trafficked or abused, and girls often face sexual violence. Life expectancy is short, grief is constant, and yet the digging continues. Kolwezi is the engine of modern technology, but also a graveyard, where people risk and lose their lives so the world can power its devices and cars. As many miners put it, "We work in our graves".

The Final Truth

Henry Morton Stanley's mission to "find Livingstone" opened the way for European control of the Congo and the violent extraction of its wealth. That same pattern, outsiders taking resources and leaving misery, still drives today's cobalt rush. Near Kolwezi, a mother named Bisette told how her son Raphael left school to dig cobalt so he could one day afford to return. He started with surface digging, earning about a dollar a day, before moving into tunnels. In 2018, one of those tunnels collapsed, killing him. Since then, grief has hollowed her life. Not long after, Elodie, a young mother with a baby, also died in the mines, another life swallowed by the same cycle of poverty and danger.

On September 21, 2019, tragedy struck again at the Kamilombe site when a tunnel collapse buried 63 men and boys. Soldiers blocked families from helping, and only four bodies were recovered. No company or authority has ever taken responsibility. As heavy rain fell, families screamed and prayed, powerless in their loss. Bisette, who had already lost her son, lost her nephew there, too. Her cry captures the truth of Kolwezi: "Our children are dying like dogs". The meaning is clear. The world's hunger for cobalt brings immense profit to corporations and consumers at the top, while leaving only death, sorrow, and broken families for the Congolese at the bottom.